A team of scientists recently unearthed a mysterious group of ‘free-floating planets’, according to a recent study published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. With the help of the data obtained in NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope, scientists spotted several ‘free floating’ planets sans any host star. For example, unlike Earth, which orbits the Sun, the newly found rogue planets are not bound to any star. Despite being kicked out of their solar systems, according to prior research, the rogue free-floating planets could hang onto nearly half their moons during the dismissal process and probably go on maintaining living conditions for billions of years. Rogue planets may have life-bearing moons.

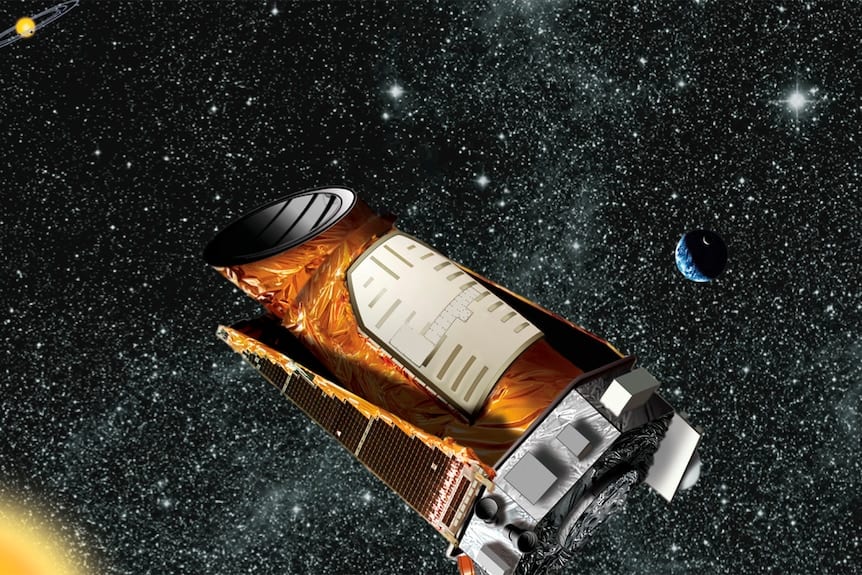

Through the whole of the two-month Kepler mission, NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope monitored a crowded population of millions of stars that were close to the centre of our Milky Way, every half an hour. It helped identify gravitational microlensing events, which indicated the presence of free-floating planets beyond our solar system.

The telescope discovered four free-floating planets and some of them might have similar masses to that of Earth. However, none of them were attached to our solar system. According to researchers, they must have originally formed around a host star, before being ejected by the gravitational tug of other heavier planets in the system. NASA even shared the names of the two planets and revealed that it added to the total of 4,424 exoplanets found so far. They named the two planets – Kepler-129d and GJ849c respectively.

The study was led by Iain McDonald from the University of Manchester in the U.K (now located at the Open University), who claims that these free-floating planets might just be wandering alone in deep space and that their planetary-mass may represent the end-states of disrupted exoplanetary systems.

How did they find the free-floating planets?

The discovery of the free-floating planets could be attributed to a technique called microlensing. “Microlensing is a tiny case of that — instead of it being a galaxy doing the bending, in this case, it’s a small, low mass object, which we can’t see, and therefore, it’s thought to be a planet” as told by the study team. Taking the help of the Kepler data, the research team identified 27 “microlensing signals” that varied between an hour and 10 days.

The method of detection used by scientists is known as microlensing, which was predicted by Albert Einstein about 85 years ago, as an inference of his Theory of Relativity.

With the process of microlensing, the light from a background star can be temporarily magnified by the presence of other stars in the foreground. It gives rise to a short burst in brightness that can last anywhere from a few hours to days, and roughly one of every million stars in the galaxy get influenced by microlensing at any random time. However, only a few are predicted to include planets. “The phenomenon is a bit like wearing a pair of glasses. Just like a normal lens in your glasses can bend light to focus things, large masses like galaxies can do the same thing — that’s general lensing,” says Cathryn Trott, president of the Astronomical Society of Australia.

Although in the words of the study team, the Kepler Space Telescope was neither designed to look for free-floating planets via microlensing nor to peer into the extremely dense star fields on the inner galaxy. To make it work this way, scientists had to brainstorm brand new data reduction techniques to detect signals hidden in the dataset. “These signals are extremely difficult to find. Our observations pointed to an elderly, ailing telescope with blurred vision at the most densely crowded parts of the sky, where there are already thousands of bright stars that vary in brightness and thousands of asteroids that skim across our field,” said McDonald.

He further added, “From that cacophony, we try to extract tiny, characteristic brightenings caused by planets, and we only have one chance to see a signal before it’s gone.”

It’s a daunting task for scientists and more often than not, it becomes very difficult to spot rogue, free-floating planets. “It’s about as easy as looking for the single blink of a firefly in the middle of a motorway, using only a handheld phone,” said Dr McDonald. Though with the help of a forthcoming space-based array from NASA called the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, along with the ESA’s Euclid mission, which is specifically designed to detect microlensing signals, it might offer scientists more evidence of free-floating planets that are similar to the Earth.

Further reading: