Scientists have found definitive evidence which suggests that two groups of ecologically important marine microorganisms could be eating virus. This study could lead to a better understanding of the flow of organic matter in the ocean.

This study published in the Journal Frontiers in Microbiology contradicts the current views about the role of viruses and protists, which are single-celled microorganisms in the marine food webs.

The Virus-eating microorganism

Ramunas Stepanauskas, who is a corresponding author said that their data shows that a lot of protist cells have DNA of a wide variety of non-infectious viruses, but not bacteria. This is strong evidence that they are feeding on virus instead of bacteria. Ramunas is the Director of the Single Cell Genomics Center at Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in the US.

The scientists pointed out that the predominant model of the role of viruses in the marine ecosystem is that of a “viral shunt”. This means that microbes infected with a virus lose a considerable fraction of their chemicals back into the pool of organic matter. According to the current study, the viral shunt could be complemented by a link in the marine microbial food web that may establish a “sink of viral particles in the ocean.”

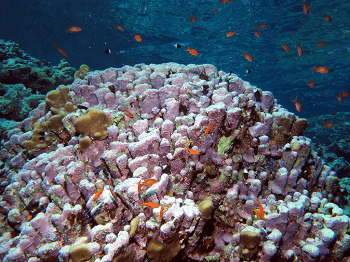

Protists. Source: Sci-news.com

This finding has implications for the flow of carbon through the microbial food web according to the researchers. Stepanauskas and his colleagues studied the sample of surface seawater from the Northwestern Atlantic in the Gulf of Maine in the US in July 2009, and the Mediterranean off Catalonia, Spain in January and July 2016. Using modern single-cell genomics tools, they sequenced the total DNA from 1,698 individual protists in the water. They found evidence of protists with or without associated DNA.

According to the study, the associated DNA could be due to symbiotic organisms, ingested prey, viruses or bacteria sticking to the protists’ exterior. Scientists said that while the technique is very sensitive, it doesn’t directly show the kind of relationship between a protist and its associate.

The researchers found a wide range of protists, some of which are alveolates, stramenopiles, chlorophytes, cercozoans, picozoans, and choanozoans. They found that 19% of the genome from the single-celled organism taken from the Gulf of Maine and 48% of genomes from the Mediterranean were found to have bacterial DNA, which means these protists had eaten bacteria. In spite of this, viral sequences were more common. 51% of genomes from the Gulf of Maine and 35% of those from the Mediterranean were found to have viral DNA.

Choanozoans and picozoans

Choanozoans and picozoans were found to be different from these groups. Neither of these contains chloroplasts and they only occurred in the Gulf of Marine sample. Choanozoans are of immense evolutionary interest as they are the closest living relatives of animals and fungi.

The researchers said that these tiny single-celled organisms were initially discovered 20 years ago, and their food source has been a puzzle. Their feeding apparatus is too small for bacteria but sufficient for viruses.

In the current research, the scientists found that all of the choanozoan and picozoan genomes were related to viral sequences from bacteria eating viruses called phages, but majorly without any bacterial DNA. They found that the same genome sequences were visible across a wide variety of species.

Julia Brown, co-author of the study at the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences said that it is highly unlikely that these viruses are capable of infecting all the protists in which they were found. Considering all this, the scientists reached the conclusion that choanozoans and picozoans probably regularly eat viruses.

Brown added that the virus is rich in phosphorus and nitrogen, and that it could serve as a good supplement to a carbon-rich diet that may include cellular prey or carbon-rich marine colloids. Scientists think that removing viruses from water may reduce the number of viruses available to infect other organisms, while at the same time transport the organic carbon within virus particles higher up the food chain.

“Future research might consider whether protists that consume viruses accumulate DNA sequences from their viral prey within their own genomes, or consider how they might protect themselves from infection,” Brown said.

Further Reading: