Who knew we could hear Space? NASA’s Chandra X-ray Center has made it possible. These musical renditions of space, called sonification were released on 22nd September 2020. Matt Russo, who is an astrophysicist and musician at the astronomy outreach project SYSTEM Sounds in Toronto said, “Listening to the data gives [people] another dimension to experience the universe.”

Sonification can help people with blindness or visual impairments access cosmic images and data. For sighted learners, it could complement the images. SYSTEM sounds has teamed up with Kimberly Arcand to create new pieces. Kimberly Arcand is a visualization scientist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass.

Christine Malec is a musician and astronomy enthusiast who is blind. She recollects the first sonification she ever heard. It was a rendering of the TRAPPIST-1 planetary system which was played by Russo in a planetarium show in Toronto. She says, “I had goosebumps because I felt like I was getting a faint impression of what it’s like to perceive the night sky or a cosmological phenomenon.” She added that music adds to data “a spatial quality that astronomical phenomena have, but that words can’t quite convey.”

Milky way into music

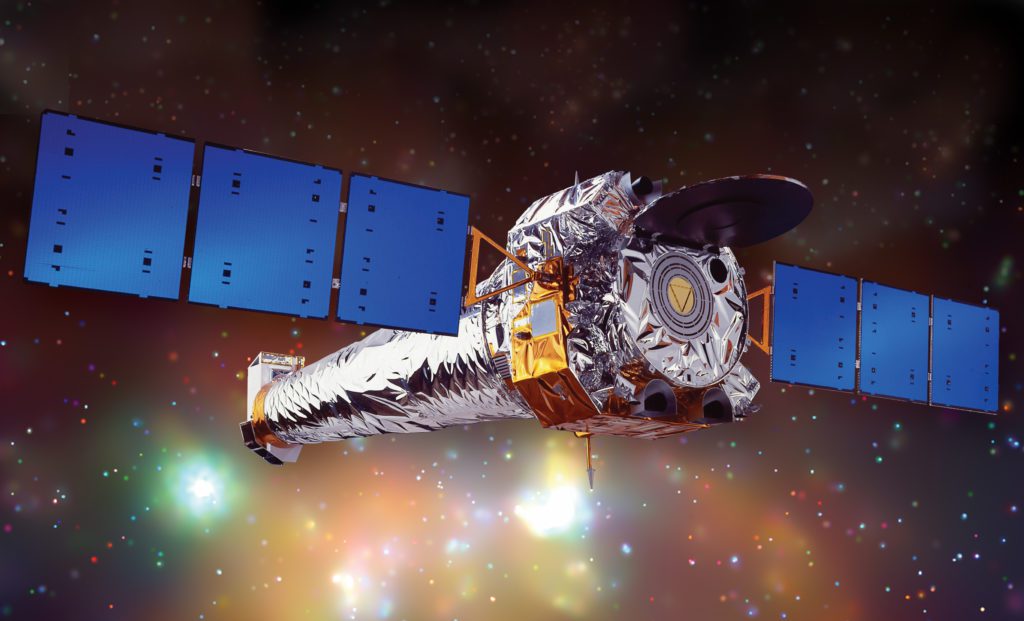

Combining data from various telescopes tuned to different types of light, the new renditions were formed. Consider the Milky Way’s Center for example. It includes observations from the Chandra X-ray Observatory, infrared observations from the Spitzer Space Telescope and optical images from the Hubble Space Telescope. We can hear data from each telescope alone or all three combined into a harmony.

The moving cursor in the image of the galactic centre shows a 400 year light expanse. Chandra X-ray observations are played on the xylophone and it traces the filaments of superhot gas. Observations from Hubble are played on the violin and show the pockets of star formation. Piano notes illuminate infrared clouds of gas and dust from the observations of the Spitzer Space Telescope.

Sources of light near the top of the image play at a higher pitch, while brighter objects play louder. The song reaches its crescendos in the lower right corner of the image around a luminous region. This is where the glowing gas and dust cover the galaxy’s supermassive black hole.

To give the observation an element of texture, the instruments were layered on top of each other. “It appealed to my musical sense because it was done in a harmonious way — it was not discordant,” Malec says.

According to Arcand, this was done on purpose. He says, “We wanted to create an output that was not just scientifically accurate, but also hopefully nice to listen to. It was a matter of making sure that the instruments played together in symphony.”

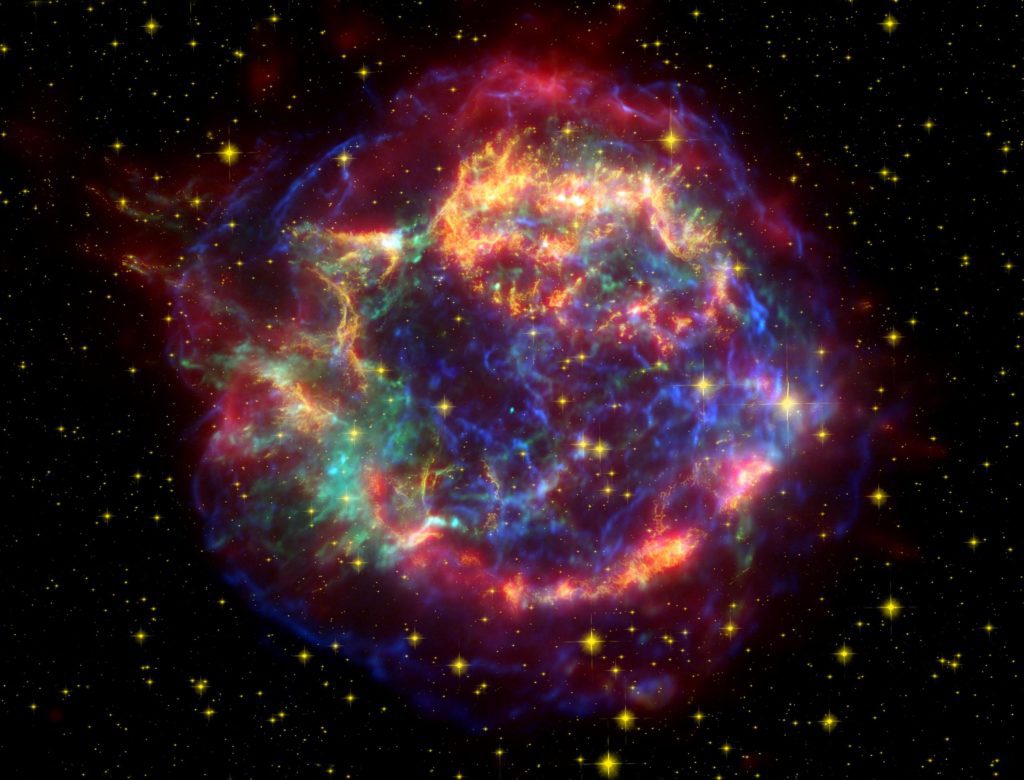

But Malec says that discordant sounds can also be educational. She explains this by referring to the new sonification of supernova remnant Cassiopeia A. The sonification uses notes played on stringed instruments to trace chemical elements throughout this great plume of celestial debris.

Malec says that those notes make harmonious music, but it’s difficult to tell them apart. She said that she would have picked different instruments to make it easier for the ear to follow. She suggests a violin paired with a trumpet or an organ.

Music and Astronomy

Wanda Díaz-Merced, an astronomer who is also at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics but was not involved in the project says that while sonification could engage the common public in astronomy, it also holds potential to help professional astronomers analyze data.

Astronomers like Díaz-Merced, who is blind, have studied stars, solar wind, and cosmic rays with the help of sonification. In addition to this, Díaz-Merced has demonstrated in experiments that sighted astronomers can better pick out signals in datasets by studying both audio and visual information together, rather than visuals alone.

Efforts to sonify data for research have been rare. Making this a mainstream research method could make astronomy more accessible and may also lead to new discoveries, she says.

Further Reading: