The global efforts to combat the ongoing Coronavirus pandemic have been largely met with mixed reactions. With no cure in sight and the prospects of a vaccine sometime away, the only weapon the world has against this menace is the social limitations that have been put in place.

The lockdowns worldwide seem to have worked, and the infection rate is not as bad as it could be. However, lockdowns and social distancing are only stop-gap measures; the only effective way to end this pandemic is either through a cure or a vaccine. The world is waiting for either to come out so that some semblance of normalcy can be regained.

In their efforts to create effective therapies, scientists have to perform a lot of tests. These tests cannot be performed on humans as there is no telling what will happen to them as a result. To this end, researchers generally use stand-ins instead of humans.

The most common of these stand-ins are mice. Coronavirus is highly effective at infecting and replicating in humans. However, this is not the case with mice. This might be good for the little furry animals, not so much for the scientists. Scientists need these mice to catch the infection for them to test their therapies on them.

Up until now, whenever the scientists tried to infect mice with SARS-CoV-2, they simply didn’t catch the disease. The researchers highly need a small biological animal model that can reproduce the clinical course and pathology observed in Coronavirus patients.

It is because of this resistance to the disease that is found in mice that scientists have largely been unable to use mice as the stand-ins. Mice are a highly probable choice for such tests because of their availability in large numbers and highly similar immune reactions to foreign agents in their systems.

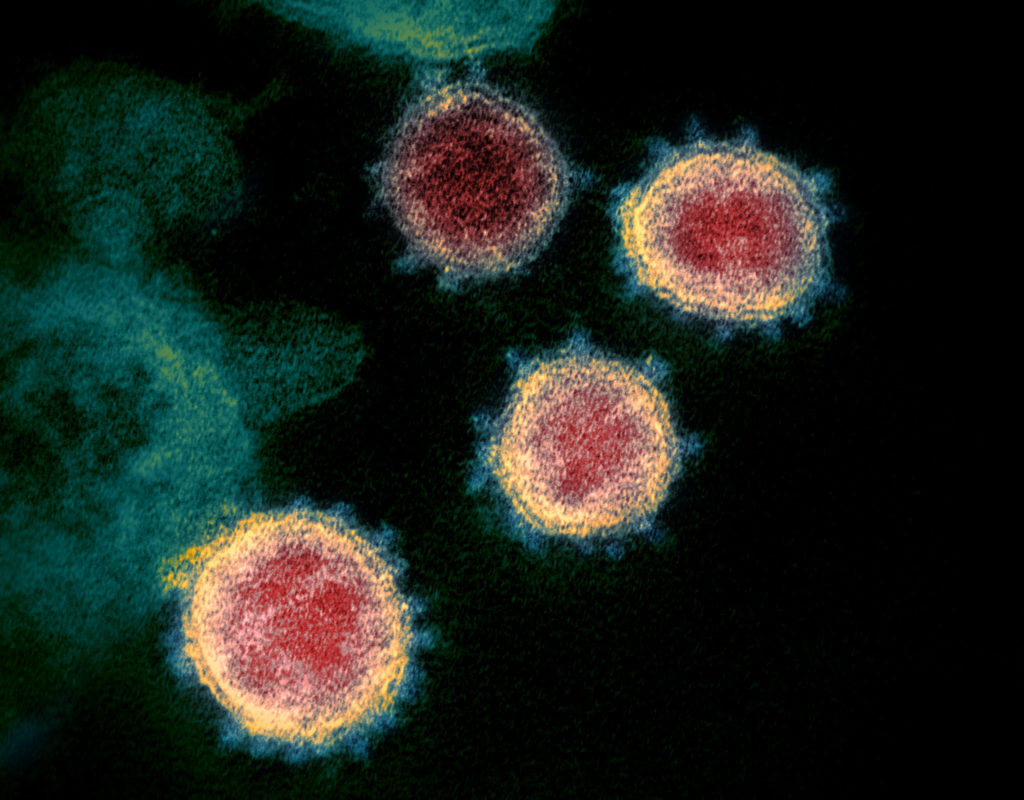

A team of Chinese researchers has used CRISPR to create mice with a human receptor on their cells. The receptor is called angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (hACE2)—this the very receptor that the Coronavirus uses to gain entry into human cells. The addition of this receptor means that the mice can now catch the disease just as well as humans.

The genetically modified mice were infected with the virus, and soon enough, scientists observed the viral RNA in their lungs, trachea, and brain. The presence of the viral RNA in the brain, however, was a little surprising as a very small amount of Coronavirus patients had reported neurological symptoms. This can prove to be a great asset in the development of potential therapies for the Coronavirus, and we can expect things to pick up pace after this discovery.

Further Reading: