Scientists say that some of our earth’s first animals may have used social networks for communication, nutrition or reproduction. Scientists from the University of Cambridge and Oxford in the UK have discovered that rangeomorphs, organisms that were in existence half a billion years ago, were interconnected through a long, string-like filament. Researchers think that these social networks helped these sea animals clone themselves. This is the first time such a filament has been discovered in such old animals.

The study published in the journal Current Biology discovered these filament networks in seven species across nearly 40 different fossil sites in Newfoundland, Canada. Alexander Liu, the lead author of the study from the University of Cambridge, called this formation a “social network”. Rangeomorphs spread in huge numbers and were very successful towards the end of the Ediacaran period (approximately 635 to 541 million years ago). Before this, almost all life on Earth had been microscopic.

What are Rangeomorphs?

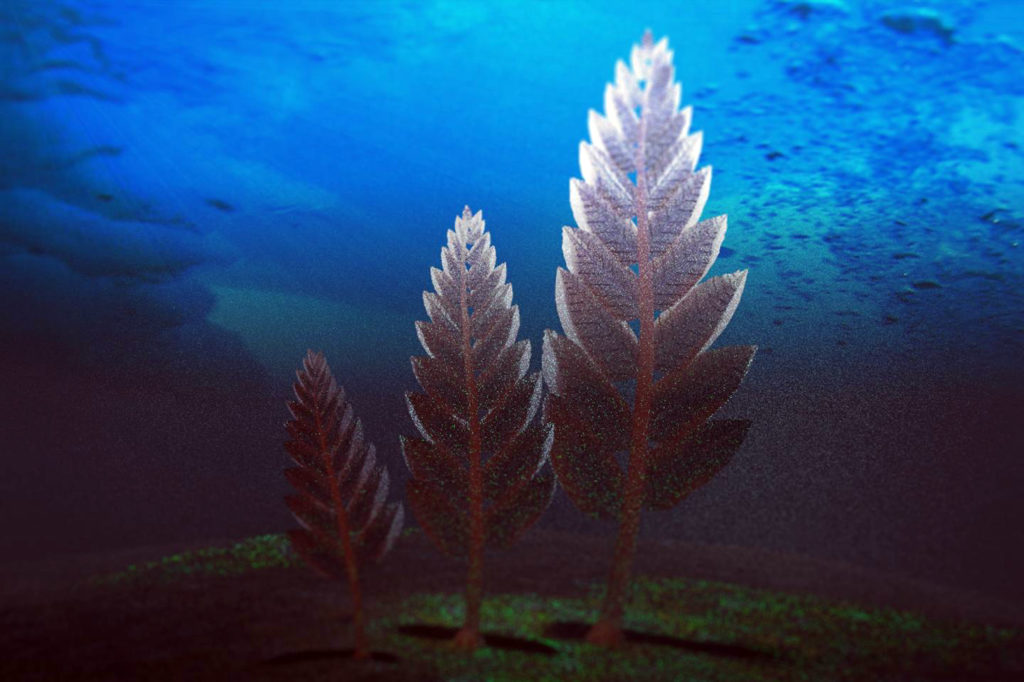

Rangeomorphs, some of the earliest animals on Earth, looked a lot like plants, but are believed to have been animals. These organisms had no mouth, organs or means of moving around. They are believed to have been shape-shifters which enabled them to dominate the Earth’s oceans for 30 million years, up until the Cambrian explosion 541 million years ago. They varied a lot in size – while some were only a few centimetres, the largest grew to 2 metres in height.

“These organisms seem to have been able to quickly colonize the seafloor, and we often see one dominant species on these fossil beds. How this happens ecologically has been a longstanding question—these filaments may explain how they were able to do that”, said Liu in a statement.

Scientists believe that Rangeomorphs dug into the mud on the ocean floor to suck up nutrients from the surrounding water, using their leaf-like branches. As Rangeomorphs hardly ever moved around, their fossils have remained intact, which makes it possible to analyse the whole population from the fossil record. The researchers found these fossils on five sites in eastern Newfoundland, which is one of the world’s richest sources of Ediacaran fossils.

Most of the filaments discovered were two to forty centimetres in height, although some were as long as 4 metres. The filaments were only visible in places where fossil preservation was exceptionally good because they were so thin. This is one of the reasons why these networks were not identified sooner. Liu, who has studied Rangeomorphs for over a decade, said the filaments were a surprise.

What did the filaments do?

Exactly what these filaments did is not clear. The researchers suggest that the filaments may have been used to provide stability against strong ocean currents. Another possibility is that they may have served as a way to share nutrients, a prehistoric version of ‘wood wide web’ (trees linked to the fungi network can share resources with their neighbours), observed in modern-day trees. Or perhaps these filament networks were utilized by them as a form of clonal reproduction like modern strawberries. This would have allowed these organisms to spread across large sections of the seafloor very quickly.

“We’ve always looked at these organisms as individuals, but we’ve now found that several individual members of the same species can be linked by these filaments, like a real-life social network,” said Liu. “We may now need to reassess earlier studies into how these organisms interacted, and particularly how they competed for space and resources on the ocean floor. The most unexpected thing for me is the realisation that these things are connected. I’ve been looking at them for over a decade, and this has been a real surprise.”

The co-author, Dr Frankie Dunn from the Oxford University Museum of Natural History said, “It’s incredible the level of detail that can be preserved on these ancient sea floors; some of these filaments are only a tenth of a millimetre wide.” “Just like if you went down the beach today, with these fossils, it’s a case of the more you look, the more you see.”

Further Reading: